While the Trump administration has done its best to undermine state authority—from clawing back grants to revoking California’s Clean Air Act waivers—state leaders can still make progress on clean transportation. Even after the administration's illegal freeze on funds and massive program cuts via the "One Big Beautiful Bill Act," there are still unspent pockets of federal money available to states. States have underutilized authorities to transfer highway funding to projects that give people healthier, easier, and cleaner options for travel, like public transit, biking, or walking.

Now, it’s a matter of using this authority, identifying these funds, and channeling them effectively. That authority is enshrined in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law that expires at the end of 2026. Historically, both parties have supported a state's right to decide how to use federal transportation funds. But today, as the Trump administration looks to consolidate power and undermine states, it is not clear what the next Surface Transportation Reauthorization will hold. States must act quickly and decisively to maximize the impact of available funds.

By using these funds wisely, states can build healthier, cleaner transportation systems, including more public transit, better cycling, and walking infrastructure.

Transportation funding is one of the biggest chunks of money that states receive from the federal government. The National Highway Performance Program alone has contract authority for $30 billion annually from 2022 to 2026.

The U.S. Department of Transportation disburses federal dollars primarily as formula funds, which are allocated to state and local governments based on a blanket formula that takes into account factors like population size, number of bridges, and maintenance needs. This October, we are likely to see new criteria for Fiscal Year 2026 federal formula dollars that include Secretary Duffy’s priorities of high marriage rates and high birth rates over traditional criteria like population and projected growth.

States can choose to “flex” funding. Flex funding allows states and metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) to reallocate federal transportation funds away from their original purpose, like highways, to other initiatives like transit, bicycling, and pedestrian infrastructure. This can be done through transfers from one highway program to another or to the Federal Transit Administration (FTA).

The most high-profile recent example of a state exercising this authority to move funds to the FTA is when Pennsylvania Governor Shapiro flexed $153 million to pay for transit in 2024. The money came from highway projects that had not yet been started, where federal dollars were obligated but not actually programmed. While the state had money sitting on the books for many years, public transit was struggling to make its numbers add up. Two decades earlier, Pennsylvania Governor Rendell had similarly flexed highway money (PDF) to support transit under parallel circumstances.

Flex funding is highly discretionary (PDF). There is no upper limit on flex funding authority, like there is with the movement of other kinds of federal dollars. However, flex funding requires significant engagement with the federal government at the district and headquarters level through both the Federal Transit Administration and the Federal Highway Administration. Given the antagonistic relationship between the U.S. Department of Transportation and states with Democratic governors, under Secretary Duffy’s leadership, this strategy is not feasible today, but other opportunities remain.

There is another, lower lift route for states to move federal money towards low-carbon transportation options like electric vehicles, transit, walking, and biking. States can transfer money across Federal-Aid Highway Programs that are administered by the Federal Highway Administration. Nationwide, state budgets are impacted by federal funding freezes, slowdowns, and program cuts. But transfer funding provides an alternative source of federal funding that states can draw from to cut transportation pollution and invest in clean transportation infrastructure.

States have used this authority before, generally to move money away from sustainable transportation projects. In 2022, the Transportation Research Board published a retrospective analysis on the use of funds from the previous two surface transportation reauthorizations (MAP-21 and FAST Act). From Fiscal Years 2013 to 2020, states flexed $13.3 billion from highway to transit projects. The major leaders in flex funding have been New Jersey (flexing 15 percent), California (10 percent), and Maryland (9 percent), closely followed by Oregon, Vermont, and New York. The states most likely to flex money to transit systemically are part of a legacy group of states that have poor air quality and need to meet air quality improvement performance measures.

States also already transfer on average 8.7 percent of dollars between Highway Trust Fund programs. Since the National Highway Performance Program is the biggest program, most of those dollars came out of highway funding. The Surface Transportation Block Grant Program is the most flexible of the Highway Trust Fund programs, so states often choose to transfer money into it. The states that used transfer authority from the National Highway Performance Program to the Surface Transportation Block Grant program were led by both Republican and Democratic governors: Mississippi, Maine, Nebraska, and Virginia were top users of transfer authorities towards flexibility and away from highway projects.

The first three years of Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding have proven to be more of the same, according to research from the Climate and Community Institute. States are transferring about 13 percent of funding out of the National Highway Performance Program. Most of that funding (11 percent) went into the Surface Transportation Block Grant (STBG) Program. Most of that funding from STBG has gone into highway expansions eligible under the block grant program, rather than electric vehicle infrastructure or other modes. The air quality mitigation program and the two explicit climate programs (Carbon Reduction Program and PROTECT) have seen funding flexed out. California has flexed only 6.5 percent ($895 million) out of the National Highway Performance Program. It has the authority to flex another 43.5 percent out of new highway build and into sustainable transportation projects.

Time is running out on the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law transfer authorities. States now have limited funding for electrification, transit, walking, and biking. So now, more than ever, states need to use available funds to support climate and vehicle electrification goals.

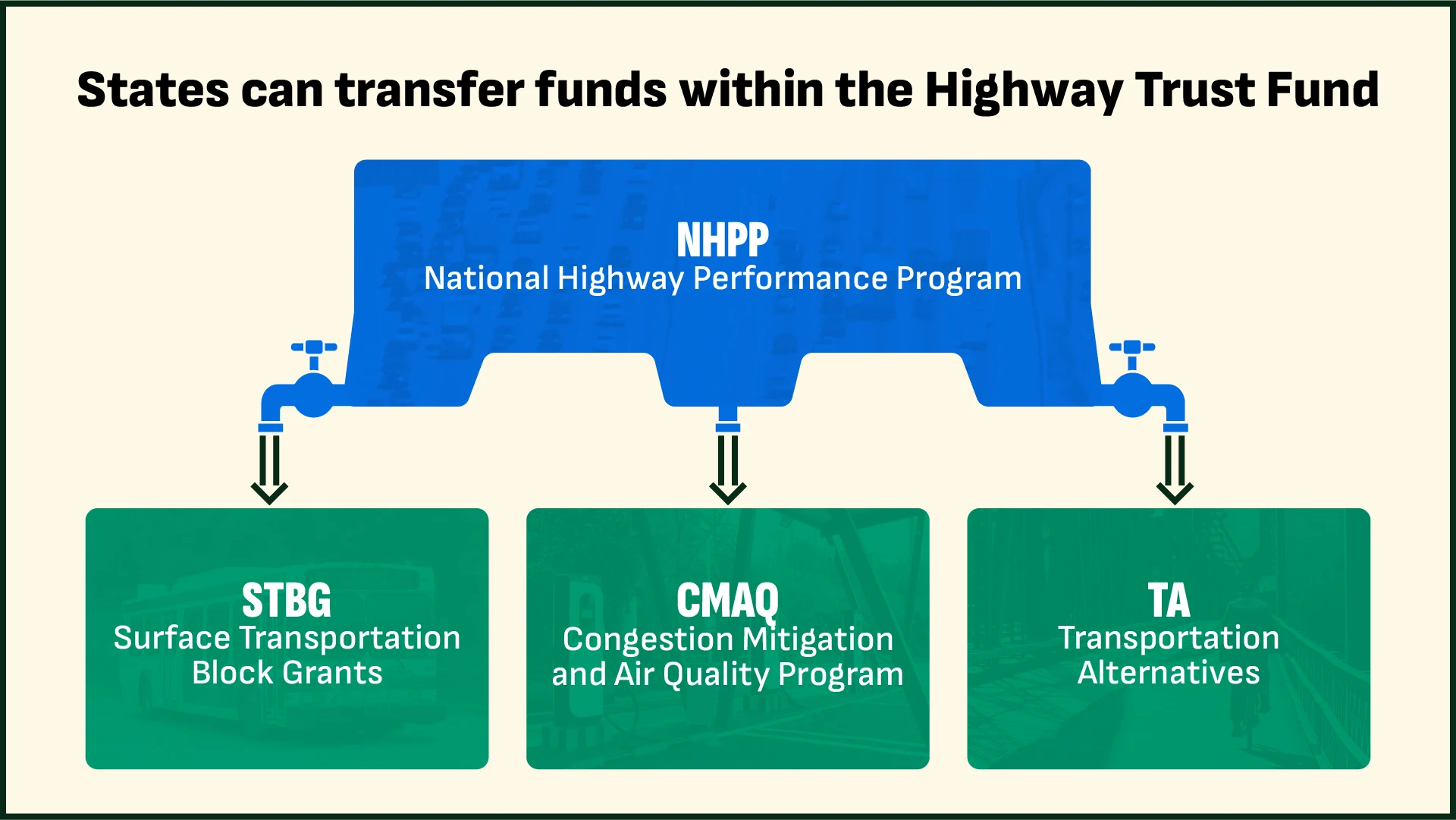

The Highway Trust Fund includes four key programs that have direct transfer eligibility. These funds are appropriated by Congress to state and local governments. The National Highway Performance Program (NHPP) can be used for projects related to highway construction, maintenance, and resilience for highway facilities. By transferring funding out of this program, states can fund projects that reduce pollution, support public transit, and allow greater mobility.

© 2025 Andrew Hartnett/Evergreen Action

By moving funds away from the National Highway Performance Program, states can bolster funding for the following programs:

The transfer of funds is a legally protected state authority (23 U.S. Code § 126). States can transfer up to half of the National Highway Performance Program dollars into other funds, including the Surface Transportation Block Grant, Congestion Mitigation Air Quality, and Transportation Alternatives programs. For states interested in building out electric vehicle infrastructure, transferring National Highway Performance Program dollars into the Surface Transportation Block Grant may be the simplest path forward. For states building out sidewalks, protected bike lanes, and long-distance commuter bike spines, Transportation Alternatives would be an appropriate avenue. And for states looking to move money into transit, transferability authority presents many opportunities to re-allocate highway dollars to both capital and planning projects.

The actual transfer mechanism is bureaucratic but simple: The state completes a transfer request form to transfer dollars out (XLS) of one Highway Trust Fund formula program into another. The form is submitted for sign-off to the appropriate Federal Highway Administration division office. Unlike flexing funding from the Federal Highway Administration to the Federal Transit Administration for transit capital projects, transfer of money across Highway Trust Fund programs does not require federal agency inter-administration deliberation. The projects must be included in the State Transportation Improvement Program documentation, and the amounts must be at or below the maximum ceiling for transfer levels. Since the right for states to transfer these funds is statutorily protected, the form is a notification system, rather than a request from the federal government.

For Fiscal Year 2025, Pennsylvania received $1.25 billion dollars for highway projects, and Illinois received $1.1 billion. Each state has the authority to put half of that towards electric vehicle infrastructure, vehicle-grid integration, bus facilities and bus electrification, sidewalks and bike lanes statewide, and even congestion pricing planning. In Pennsylvania, $625 thousand of NHPP money transferred to STBG could triple the build-out of electric vehicle charging infrastructure that the state had planned under the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) formula program for 2026. The state could electrify another six counties—or 180 highway miles.

Electric vehicle charging station in San Francisco, California. Justin Sullivan/Getty Images News via Getty Images

In California, Governor Newsom has pushed back against the rollback of the Clean Air waivers that California used to regulate vehicle efficiency and emissions. The Governor issued an executive order and game plan (PDF) on how the state will continue to deploy electric vehicles despite this federal setback. The report calls out the state’s opportunity to “utilize qualifying federal funds for ZEVs [zero-emission vehicles] and supporting infrastructure when possible.” As it should. California received a whopping $2.6 billion in federal funding this year just for highway improvements. In addition, California received $1.3 billion, already allocated to the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program, which can include a broad array of projects, including funding electric vehicle infrastructure. Governor Newsom could immediately exercise the authorities already available to him to support the statewide prioritization of electric vehicle buildout.

Moving funding from highways to sustainable transportation projects is a win-win for transportation affordability, transportation choice, and decarbonization. Transportation is the single highest polluting sector in the United States, contributing 28 percent of our nationwide emissions. Highways, especially new highway projects and lane expansions, mean more cars on the road. More highways also mean fewer opportunities for both people and goods to use other, lower-carbon transportation modes. Highways cut across communities, creating roadblocks for public transit, walking, and biking, reducing safety for all roadway users and lengthening commute times. Highways are bad for our economy and our climate.

Transferring dollars out of highway projects and into sustainable transportation both reduces pollution and increases transportation access. Projects like the build-out of electric vehicle infrastructure, sidewalks, bike lanes, and public transit also produce more and higher-quality jobs both within the construction and transportation sectors, and because of increased access to job centers (PDF).

The future of transfer funding is uncertain. States must act now to move available funds into sustainable transportation projects and make use of their right to transfer funding.

Liya is the senior transportation policy lead for Evergreen. Liya previously advised on policy for the US Department of Transportation Office of the Secretary and for the California State Transportation Agency.

Medhini is the writing/editing digital lead for Evergreen. Through powerful storytelling, she hopes to help move the needle on climate policy and contribute to our collective fight for a livable planet.