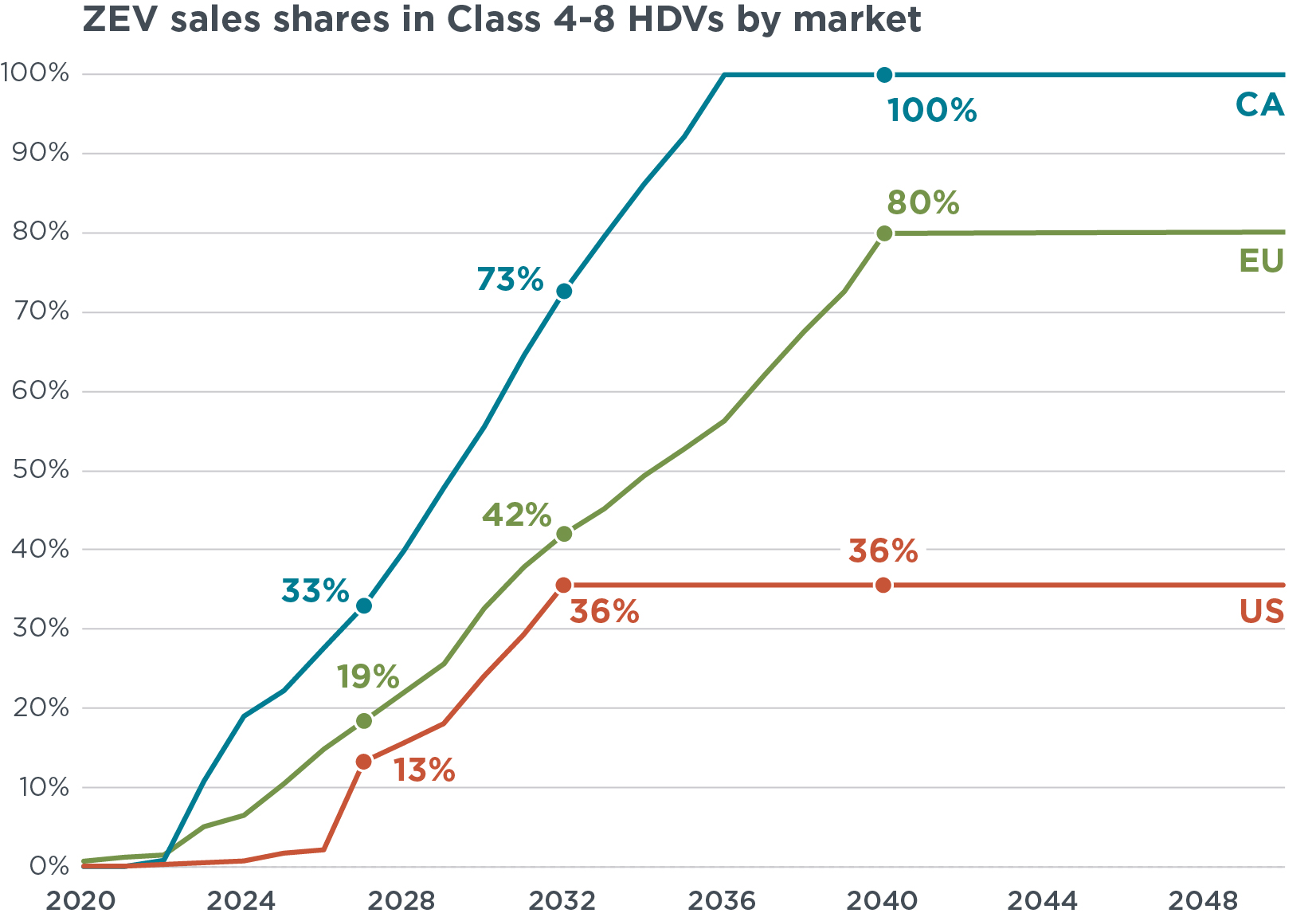

EPA needs to adjust its carbon pollution standards to, at the very least, align with the ACT trajectory; to support rather than undermine these efforts; and to consider a standard that would achieve 100 percent zero-emission trucks soon thereafter. After finalizing the rule, EPA can go one step further and close a series of loopholes in its national smog rules that allowed polluting trucks to stay on the road, just as California and industry have agreed to do.

And then there’s the matter of not just setting strong standards, but getting it done: EPA, as well as the Departments of Energy (DOE) and Transportation (DOT), have significant funding opportunities through:

What’s great about these funding streams is that much of it is designed to directly benefit communities of color and advance environmental justice through initiatives like Justice40. But so far, these funds are not being deployed strategically enough to link up with increased regulatory ambition. President Biden must connect these funds to clear commitments in our nation’s freight corridors, laying the groundwork for ambitious standards and safer, healthier communities.

The White House must use its convening authorities to align these funds and strike key agreements among utilities, ports, states, truck-makers, government and labor groups, and communities to accelerate building essential charging infrastructure.

But What About the Cost of Heavy-Duty Vehicle Electrification and the Need for Charging Infrastructure?

First, electric vehicles are actually cheaper to run in the long term: They last longer, have more affordable parts, and aren’t impacted by volatile gas prices. And more affordable and larger batteries will only grow this trend in the future. In other words, it’s actually in corporations’ interests to transition to electric trucks—but they also have an obligation to do so. If we want a more robust supply chain, we need to increase production and cut costs. Electrification can help do that.

Second, the best way to increase the rapid build-out of charging infrastructure is to pass a strong rule requiring zero-emission trucks, which is the investment signal the private sector needs. Plus, all infrastructure does not need to be built at once. Aiming funds and White House-led agreements at infrastructure in key ports and freight corridors would be more than enough to support most trucks, which are concentrated in these areas. A smart phase-in, combined with a clear investment signal from strong rules, will get it done.

Beyond this, we’ve already laid out a bunch of federal investment opportunities to ensure that the heavy-duty vehicle charging network is extended and ready. The IRA and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) investments make it even easier by supporting progress in zero-emission heavy-duty vehicle manufacturing, purchasing, and expansion of charging and fueling infrastructure. Moreover, they boost parallel private investment in energy, infrastructure, and vehicle production and purchases.

Lastly, let’s nip range anxiety in the bud. The fact is most heavy-duty trucks (about 70 percent) operate within a 100-mile radius, meaning we don’t need quite as many chargers as we might think and most trucks won’t have to charge any more often than they would fill in gas. New analysis from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) shows that the U.S. can electrify far more of the trucking fleet than EPA has proposed with focused infrastructure investments in the biggest ports and trucking corridors. In fact, infrastructure deployed on less than 10 percent of the highway network would get almost double the electrification that EPA’s proposal forecasts, proving industry bluster on infrastructure is just plain wrong.