Infrastructure Needs

EPA Clean School Bus Program funding will largely be allocated towards the costs of actual school buses, along with a set allotment for charging infrastructure per bus. However, as deployment of electric buses accelerates, broader power upgrades will likely be required at many schools to support increased electricity demand. Governors and state agencies should work with Public Utility Commissions (PUCs) to prioritize upgrade site assessment and upgrade requests from school districts.

States may want to consider allocating funding towards expenses not covered by the federal program.

States are also currently finalizing their plans to invest their National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure funds (NEVI) under IIJA. States should consider how their plans could support school buses specifically. As a nationwide charging network takes shape, states should ensure that school districts will be able to charge their buses outside of their home lots/depots, such as when on longer-distance field trips.

States Stepping Up with Policy Goals and Supplemental Funding

Governors should also consider setting statewide school bus electrification goals. Such goals can inject urgency throughout state agencies to remove barriers to school bus electrification, and can send a signal to districts and industry alike about the future of pupil transportation in their states.

Over the last year, a number of governors and gubernatorial candidates have advanced statewide school bus electrification commitments. In her Healthy Climate Plan, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer set a target for all new school bus purchases to be electric by 2030. New York, which has more school buses on the road than any other state, recently enacted legislation requiring all purchases to be zero-emission by 2027. In Massachusetts, gubernatorial candidate Maura Healey’s climate plan sets an ambitious target of 2030 for statewide deployment of electric school buses.

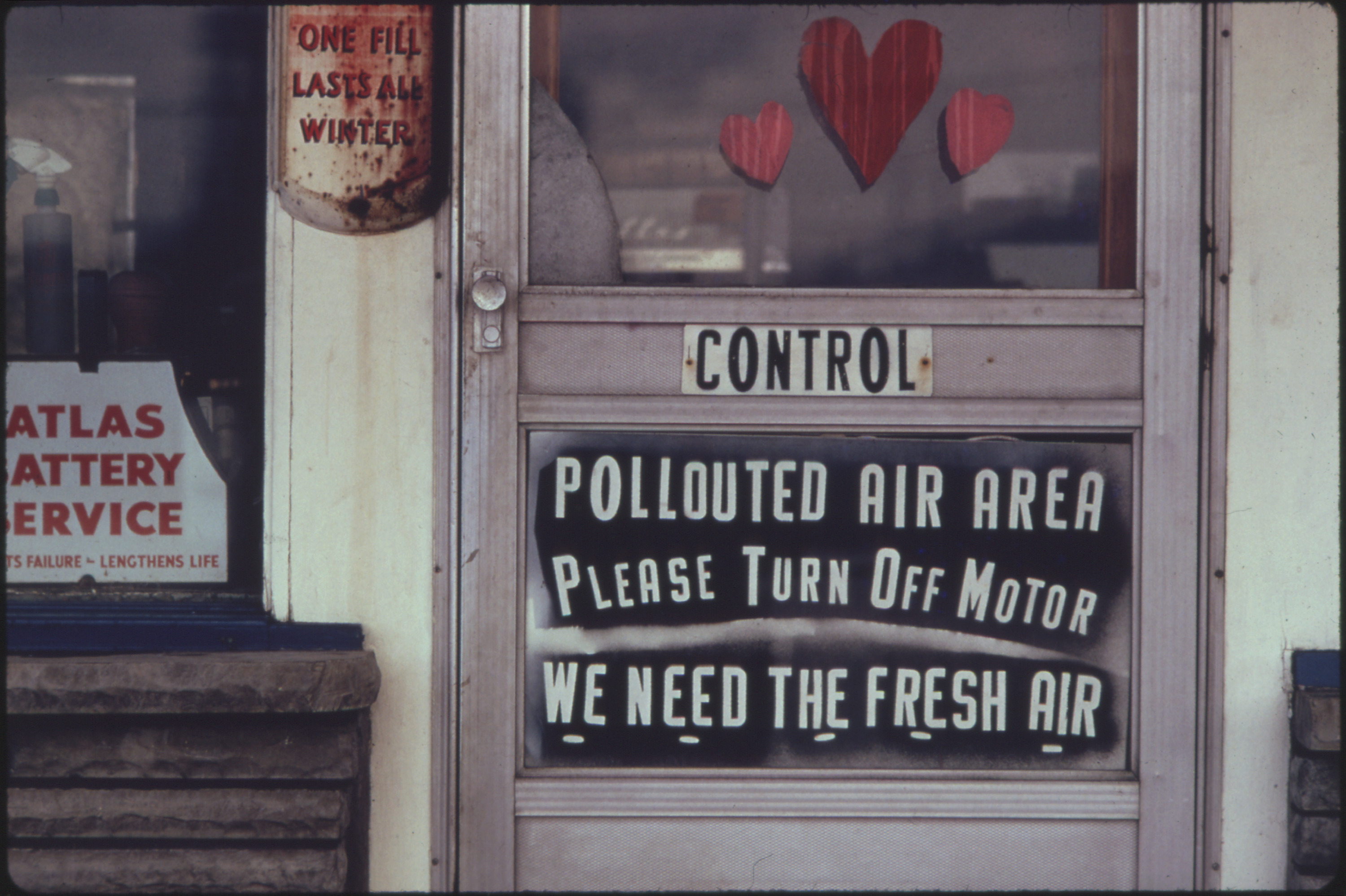

Additionally, where possible, states should consider deploying additional funding to support districts through this pivotal transition. The goal of public funding should not be to subsidize the conversion of every school bus nationwide, but to spur a cycle of mass adoption where demand increases, mass production/assembly ramps up to reduce the cost of electric buses. Although electric buses are currently more expensive than conventional buses, parity on total lifetime/ownership cost is expected within the decade. Public funding should also be prioritized and more generous for environmental justice communities.

Many states moved forward with significant state appropriations for school buses this year, including California, Colorado, New Jersey and New York. Connecticut is specifically considering a matching program that could help fund infrastructure upgrades not covered by the EPA. This is a novel approach that other states may want to examine.

At the very least, states should examine any of their existing funding streams that support school bus electrification and move to eliminate any subsidies for “alternative” fuels that still emit greenhouse gas pollution, like propane and natural gas.

Where legislative appropriations are not feasible, states can consider a variety of other support mechanisms, including via utilities and PUCs. In Illinois, for example, the utility ComEd recently submitted a beneficial electrification plan to the Illinois Commerce Commission. This plan fulfills a requirement of the Climate and Equitable Jobs Act and proposes significant investments in electric school buses. Moreover, additional federal funding may be available via certain buckets of transportation formula funds.